After reviewing several watches, and even a film, I am about to add a third string to my bow of impostures and now pretend to be a book reviewer. You have been warned and should only keep on reading at your own risk!

At the end of last month, the renowned watch industry historian Pierre-Yves Donzé released a book that immediately made headlines in French-speaking Switzerland, from newspapers to television: La Fabrique de l’excellence, an in-depth historical study of what has made Rolex’s unparalleled success.

The widely praised book is not yet available in English (although an English version is apparently in the works). For that reason, and also because not everyone may feel like reading nearly 300 pages of factual, industrial history — may it be about the Crown — I thought I would tell you about it – what I liked, but also what I found was missing.

Why this book matters

It is hard to deny that Rolex is the watch company that captures the most attention, both among aficionados and muggles. Yet, being owned by a private foundation, it has no obligation to publish any of its secrets. As a result, very little is known from behind the scenes. Some excellent books have been published, such as Gisbert L. Brunner’s The Watch Book, Rolex, but they are typically coffee table books serving the Kool-Aid, with no or little critical perspective. More recently, Brendan Cunningham’s Selling the Crown went in an opposite direction, denouncing what its author considers as the brand’s overly aggressive marketing practices. Limited in scope to a specific aspect and period of Rolex’s history, it is not comparable, as a scholarly exercise, to Donzé’s extensive research.

Pierre-Yves Donzé is somewhat of a legend when it comes to watchmaking history. The La Chaux-de-Fonds-born historian, now a professor at Osaka University, has written several books about the Swiss watch industry, from its early to present days, all considered references in their field. These include A Business History of the Swatch Group, The Business of Time, Selling Europe to the World, as well as several others not (yet) translated into English.

La Fabrique de l’excellence, published by Livreo Alphil, is a true historian’s book. Circumventing Rolex’s covertness, Donzé goes to great lengths to document with precision dozens of milestones in the brand’s history: company formations, technological patents, brand registrations, supplier acquisitions, and organizational restructuring. From the inception by the visionary founder Hans Wilsdorf at the beginning of the past century all the way to the purchase of Rolex’s leading retailer, Bucherer, at the end of last year, the full story is covered. Sources include the Musée international d’horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds, the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, the State of Geneva Archives, and Swiss Federal Archives, among many others. There is no denying this is very serious work, as its 607 footnotes attest.

Controversy from a footnote

One of those footnotes led to a controversy as soon as the book was released. On page 122, Donzé explains that the British government denied export visas for Hans Wilsdorf’s watches on the basis of his sympathy for the Nazi regime. Wilsdorf was a British citizen of German origin. The suspicion stemmed from the allegation that his brother was active within the German Ministry of Propaganda. A Geneva police report subsequently stated that Hans Wilsdorf, while not active in propaganda himself, was a “fervent admirer” of Hitler’s regime.

As Donzé pointed out in interviews, there is so little evidence at this stage that it is difficult to evaluate the importance of the allegations. That said, it is by no means a trivial matter. I found adequate the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation’s response when contacted by the Swiss newspaper Le Temps. It stated being “surprised discovering the report’s content in strong contrast with what (we) know of the founder” and “taking the matter seriously.” It has since commissioned an investigation, currently ongoing.

Because so much of Rolex’s legend is built around the visionary personality of its founder, and given the symbolism associated with watches in general, Rolex especially, I look forward to the findings. Until then, in a world of rumors and fake news, it is equally important to not jump to conclusions.

What is missing from a watch enthusiast perspective

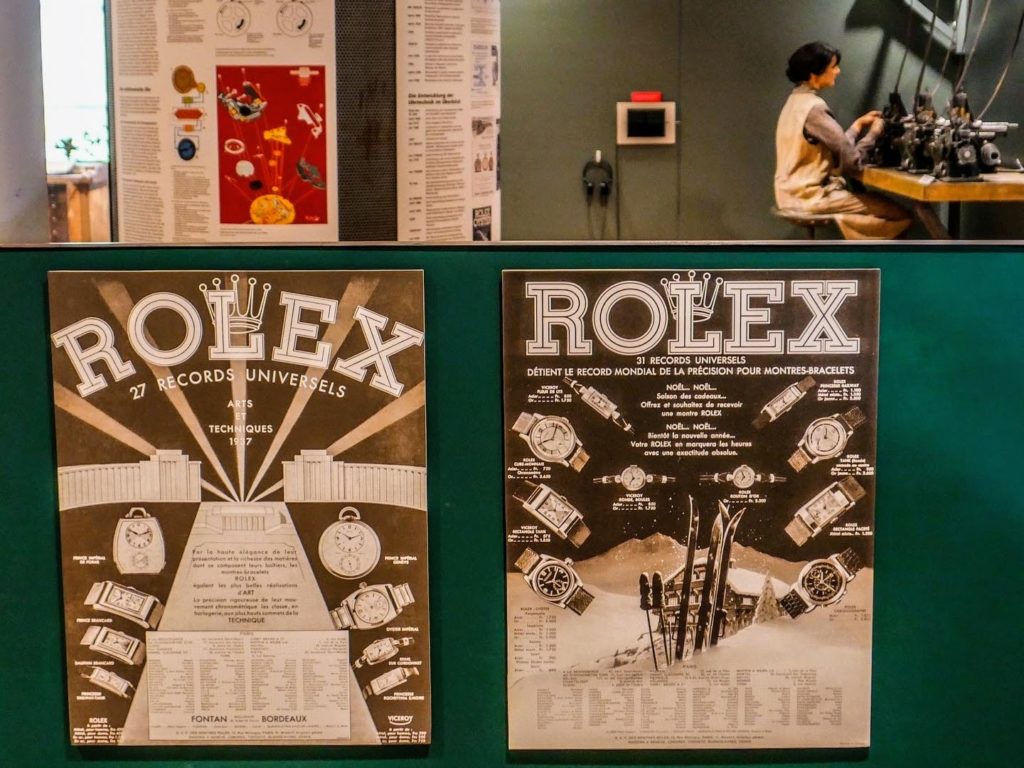

The main thesis of the book is that over the decades, Rolex has successfully created a narrative that goes beyond watchmaking: “a Rolex is an exceptional watch, for exceptional people.” Donzé stipulates that this took place, first, by creating a highly compelling product over the first half of the twentieth century and then consistently positioning it as an attribute of excellence for the world’s high achievers over the second half. Perfectly documented and rendered in his crisp and engaging style, the author makes a strong case. Yet, some of the Crown’s uniqueness is unfairly, even if not voluntarily, undermined.

Donzé writes that “before being a watch, Rolex is a narrative, showcasing the genius of an entrepreneur and the exceptional quality of its innovations”. While he lists various efforts over the years to enhance the technical competitiveness of its watches, he does not sufficiently highlight how the company ended up reaching a class of its own in that respect. It is not about being good enough, it is about being the best. As anyone who has owned watches from both Rolex and other brands knows, the consistency, performance and reliability of anything Oyster is essentially unmatched in the realm of mechanical watches.

I often say to people new to watches when they struggle to understand why I respect Rolex so much — despite resenting what it is often associated with (conspicuous wealth, flippers): “If I notice something is wrong with any of my watches, I wonder what broke; unless it’s a Rolex, in which case I wonder what I did wrong setting it.” The intrinsic quality of its pieces is what has truly earned the deep respect watch collectors have for Rolex. Not only does the company deserve full credit for this, but I was hoping to read about how it happened – the processes, methodology, research, development, testing, and more generally the zero-compromise mindset at the source of its long term success.

In a similar vein, the brand’s iconic models are explained as a strategy: build something great and stick to it. I wanted to learn how these “somethings” were made great – the thinking behind the use cases, design principles, and the philosophy of innovation versus iteration. Equally, while the book documents how Rolex stayed focused on mechanical watches and only invested in electrical watches as a hedge, it does not explain why Rolex decided to stick to the former when the rest of the industry was convinced the latter was the future.

Closing thoughts

Overall, La Fabrique de l’excellence is a great book. First, it can only be applauded for the serious and deep research that went into it. I am always amazed, reading Pierre-Yves Donzé, at how he finds the patience to study such disseminated information so minutely. Second, it is very well written, making it an easy read for anyone obsessed with watches. It took me three days, and I am by no means a particularly fast or voracious reader.

My only regret, as expressed above, is the lack of depth on product matters. Marketing is essential to understanding Rolex, it goes without saying, and I for one am surely unconsciously more subject to it than I like to admit. Still, the intrinsic quality of Rolex watches deserved to be explored, and explained, more deeply. I understand that historian-grade data on that may be hard, even impossible, to find. But I am not sure the product angle was sufficiently taken into account in the first place and yet, as a watch enthusiast, it is the one I care about the most.

L’auteur le précise bien, en préambule; il ne lui est pas possible d’avoir accès aux archives internes de l’entreprise. Seule petite lucarne, les archives d’une université américaine où sont déposées les documents de l’entreprise en charge de la publicité mondiale (sauf aux Etats Unis, pendant un temps) de la marque. Les publications des syndicats ont également été utiles, sur Bienne. Fait intéressant à relever, Oméga, jusque vers les années soixante, dépassait Rolex en production. Et je ne savais pas que le fameux Alfred Chapuis était très proche du propriétaire de Rolex. M. Donzé ne manque pas de relever que les fascicules “vade mecum” édités par Rolex à l’époque et co-écrits par A. Chapuis ne sont pas toujours très fiables.

Merci beaucoup pour votre contribution !

I look forward to reading the English version. But I agree that the intrinsic quality of Rolex products must be explained to fully account for its success.