To the casual watch collector, the name Estoppey-Addor might not sound familiar. But for those in the know, it stands as one of those companies that make the intricate world of watches even more captivating. Although the Bienne-based family business, established 144 years ago, does not produce any watch parts, it makes them better, both in terms of aesthetics and durability. And while for confidentiality purposes none of their customers’ names can be revealed, trust me: if you love watches, you most likely own or aspire to own pieces that have been through the hands of the folks at Estoppey-Addor.

A short walk away from Omega, Swatch, Armin Strom and Urban Jürgenssen, I passed by the pastel green building probably a hundred times since moving to Bienne, six years ago. I never would have imagined the Harry Potteresque activity that takes place behind its doors: dozens of bassins with a never-ending procession of colorful concoctions giving watch components their final appearance thanks to the technique for which Estoppey-Addor is renowned: electroplating.

Electroplating: Why and How

The first thing I asked when I met Sandrine and Cyril Estoppey — the siblings who are respectively CEO and CTO of the company — is: why all this coating? While I already knew that plates, bridges and balance wheels don’t grow on trees in the Jura mountains, I must confess I never thought that almost every single part of a mechanical movement receives some form of coating at the end of its already complex production process.

One reason for this is protection. Like most metals, copper — the most common material used in a watch movement — is subject to corrosion. While a water-resistant case would normally protect its content from this risk, brands prefer to be on the safe side: a damaged gasket or a wrong manipulation by the user of the crown or pushers could lead to humidity finding its way in. Even during assembly and service, when parts are frequently washed, a minuscule drop of water may accidentally remain on a part, unseen. Then, of course, especially when the movement is visible through an open caseback (an increasingly popular feature), there is the aesthetic aspect: gold, rhodium and chrome coatings are regularly used to embellish movement parts.

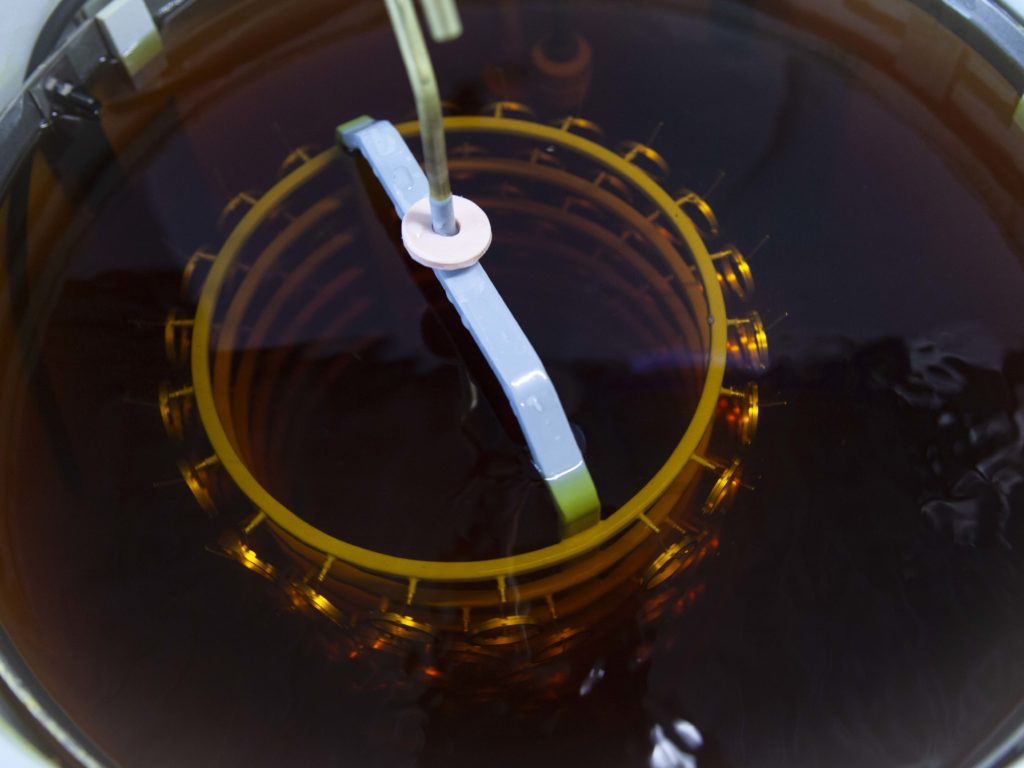

Electroplating uses electric current to deposit the metal coating. The watch part to be coated is the negative electrode, and the metal for the coating the positive one. Both are immersed in an electrolyte solution containing ions of the coating metal. When current is passed, positive metal ions from the solution are attracted to the negative electrode and deposit on it. As the coating metal dissolves, it replenishes the metal ions in the solution. The result is a uniform and controlled coating.

A Concrete Example: the Electroplating of a Rotor

Does this sound a bit abstract? Let’s take a concrete example. To avoid disclosing any secrets, we’ll look at a rotor that Estoppey-Addor produces for demonstration purposes, showing clients what they can offer. The rotor in the picture below is originally produced in brass and delivered to Estoppey-Addor. There, the first step is applying nickel, which is then followed by a gold coating. The mixture for the latter is made of actual gold, which I found surprising considering that in fact, as you’ll see, most of it is then covered. According to Cyril Estoppey “while there is a cost, the quantities are so small that it remains the most efficient way of producing.”

Before applying the final coating, the engraved part goes through a process called épargne, in French, translated as “stop-off”. A layer of non-conductive material is applied to the engraving so that it does not get coated during the next step of electroplating. It is the only section that will remain visibly in gold. The rest will get covered during the final step of electroplating with the application of a layer of black chrome.

Family Style

If I were to describe how work is done at Estoppey-Addor in two words it would be “hands-on”. Everyone is busy doing something, moving a basket from one mixture to the other, inspecting the recycling tanks or examining under a microscope the quality of each piece from the latest batch. The siblings running the company are no exception, spending as much time on the floor with their employees as in their office upstairs. “That helps us understand what is truly going on, and anticipate,” explains Cyril Estoppey. “When a problem comes up, we are not taken by surprise”.

The proximity with the production teams also has another, deeper, explanation. “We have our vision, inherited from our parents and grandparents. We can’t expect the same from our employees unless we are close to them, and pass it on”, Sandrine told me. For that reason, the duo clearly stated that they don’t want to grow beyond “family size”. With a team of almost 40 now, that means maybe a few more. “We don’t want to be 150 and lose our individual relationships,” the CEO added.

If the notion of family is important at Estoppey-Addor, it’s not just because the company is run by a sister and a brother. Established in 1880 by Louis Estoppey, the company is today the oldest electroplating specialist in Switzerland. Originally focused on the gold plating of movements, its customers from that era included Louis Brandts & Fils (a company later to be known as Omega) and Zenith. When Louis married Lina Addor from Sainte-Croix in 1886, he added her name to the company’s. While it’s unclear to what extent this was out of egalitarianism or because her name reminds of gold-plating (“dorage”) in French, the fact that the company 138 years later is run by a woman shows that Estoppey-Addor has been ahead of many when it comes to gender. Back in 1908, Lina Addor, then a widow, had continued to run the business on her own before her eldest son, Henri-Paul, joined her.

Sandrine and Cyril Estoppey are the fifth generation in the family running the company. She has been CEO since August 2012 while her brother, who had started working as an electroplater the year before, took responsibility for overall production. Even if the company aims to stay small, the future will inevitably require some growth, and maybe a change in location. The current buildings, extended three times over the years, are simply getting too narrow for the increase in demand.

Planning Ahead

While the facility dimensions may not be there yet, the company felt future-ready to me on two important fronts. One is recycling. There is basically a shadow factory, in the basement, with almost as much machinery as there is upstairs, entirely dedicated to collecting and recycling production residues. Pipes, tanks and dashboards are lined up across hundreds of square meters, making sure Estoppey-Addor is compliant with ISO norms and other regulatory requirements.

The other future-proofing that struck me is how the company has managed to diversify its activities beyond watchmaking. Like with many other micro technology players in the region, the medical field has become an area for further growth. The automotive industry is also among their clients. Still, watches remain at the core of both the business and the culture at Estoppey-Addor.

So Swiss

I often wonder how Switzerland manages to maintain so much of the different stages of watch part production within its borders. Sure, whether or not brands like to admit it, there is a lot happening in Asia. But the breadth and depth of what is still taking place locally, right here in the Jura valleys, never ceases to impress me.

When I ask people why they think it’s the case, I typically get two responses. One is about quality: the unique Swiss know-how, often passed on from one generation to another, can’t just be easily replicated, even with large investments. The other one is the convenience of being able to jump in the car — or even walk — and show your supplier or your customer what exactly is going on, iteration after iteration, until you get it perfectly right.

More than any explanation anyone could give me, walking through Estoppey-Addor is an even more powerful answer to that question. No matter how sophisticated the machines, with all the physical and chemical variables at stake, the reality is that two batches are never exactly the same. The team’s experience and instinct is what makes the difference. Likewise, being able to quickly drive, or sometimes even walk, to the customer to show them various options or the final result is priceless.

As I sit on the train, finishing up this article, I’m looking at the watch on my wrist. Based on what I got a chance to see during my visit, I’m pretty sure some parts of it went through the hands of Sandrine and Cyril Estoppey’s teams. Thinking of all the hard work that went into the mere coating of those components reminds me of why I love watches so much: the insane level of human input that — when done right — goes into making each and every single one of them.

Photography by Jeanne Grouet for Time Files. As a sidenote, it was particularly enjoyable working on this article about a sister & brother run company with my very own sister (and talented photographer!).

This is super interesting. Great to learn more about the behind the scenes of the industry

I had no idea any of this was happening as part of the watchmaking process!